BY MACKENZIE LORKIS

Jessica, one of the other UCEAP students at Doshisha, interned at a tea farm in the remote village of Wazuka for three months before our program began. I was lucky enough to travel back to the farm with her on one of the first days we got here and learn all about Japanese tea farming!

From Imadegawa Station, where Doshisha is, we traveled to Kyoto Station and got a train towards Nara. After about an hour of travel, we boarded a small bus and drove another half hour to Wazuka. The drive was absolutely gorgeous, with abundant tea fields, flowing rivers, and blossoming sakura everywhere we looked.

First, Jessica showed us some of Obubu’s tea fields right outside of their house. She explained that tea must be picked with the pads of your fingers, rather than the nails, because ripping the leaves risks oxidizing them. This is super important because the variation in teas is actually due to oxidation! Green tea is oxidized the least, and black tea the most, but they actually all come from the same leaf.

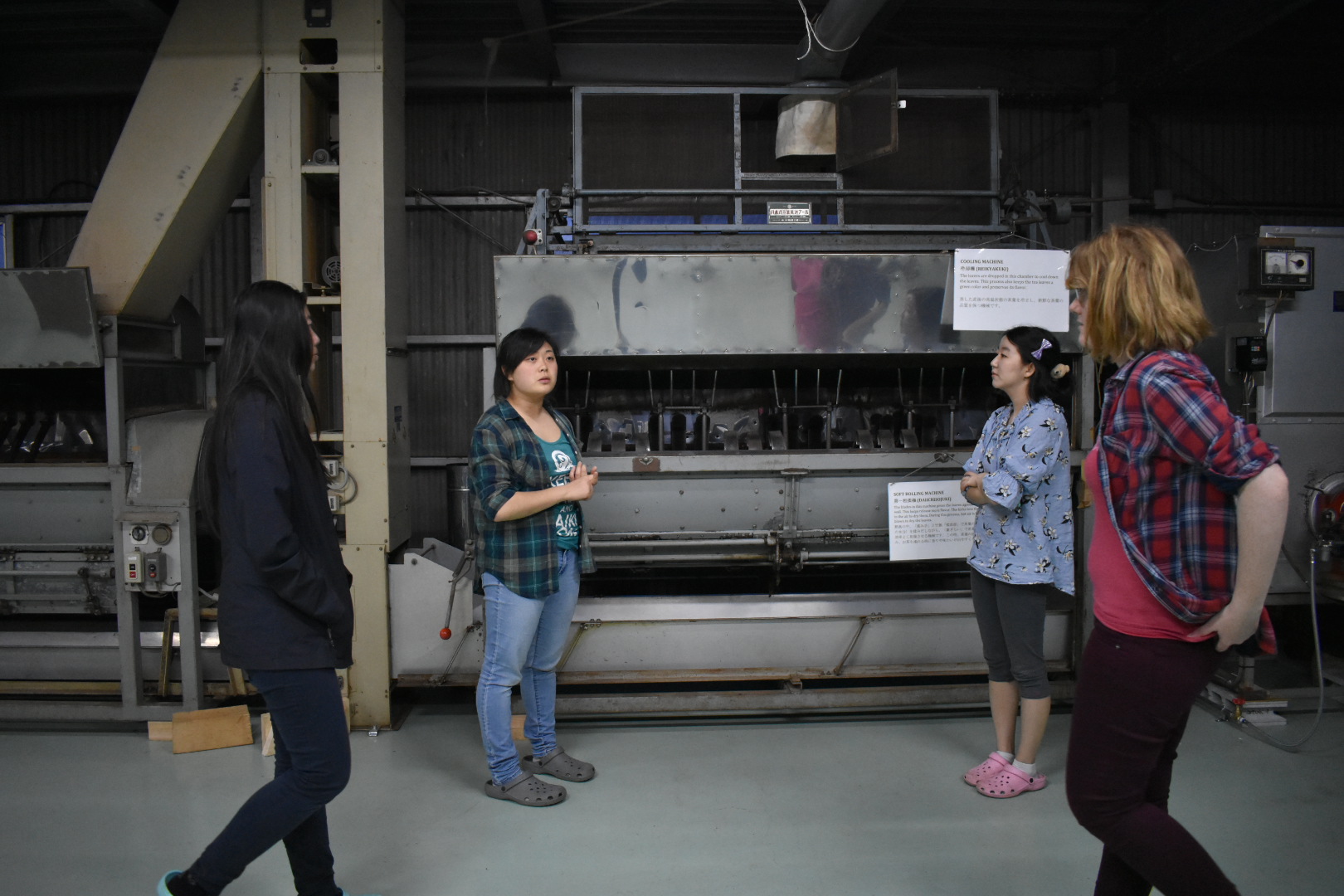

After looking around the fields Jessica took us to the processing area and explained how the tea is processed. It goes through several machines that ultimately work to dry the leaves at a very high temperature without drying them out. Tea must be kept at a very specific moisture level (about 5%) and it is very important to keep the leaves from becoming too wet or too dry.

Once it got dark, Hiro-san, one of the owners of Obubu, drove us in the back of his truck back to the house. Jessica brewed us a few types of tea to sample. First, we tried sencha, the most premium type of tea in Japan. The leaves are prepared by hand in a grueling six-hour long process. You can watch a video (here) of farmers in Wazuka preparing sencha. The leaves are rolled into a needle shape, which is specific to Japan. Originally, this was useful in carrying tea from Kyoto, where it was farmed, to Tokyo, which was the capital during the Edo period. If you put sencha on your tongue, you can feel it unfurl- it fees like a pop rock! This kind of tea is highly prized due to the artisan labor involved in its creation.

We also tried XX, which is tea mixed with roasted rice. This was originally viewed as a people’s tea because the rice made it cheaper, and it has a lovely nutty taste. Next, we tried XX, a rare Japanese black tea. When Japan opened to England, they wanted to export a tea that would appeal to Western consumers more, but green tea was actually more popular anyway. This was my favorite tea because its naturally sweet and super delicious. It actually is more red than black, even though it has the same flavor profile as a black tea, because of the water. Water in Asia is softer than in Europe, meaning it has less minerals; when mixed with the tea leaves, it results in a red-colored tea rather than black.

Finally, we each had a chance to brew matcha. Though we didn’t practice a formal tea ceremony, the way in which matcha is brewed is extremely important. We each got a bowl, which is handmade in Kyoto with gorgeous designs, and a bamboo brush called a XX. First, you soften the bristles in water so they don’t bend. Then, you use a traditional spoon called a XX to take about a teaspoon of matcha powder and put it into your bowl. Then, we poured a little water into the bowl and mixed it with the matcha in order to create a paste. When we finished, we poured more hot water and quickly used the brush to make the tea frothy. The more umami flavor present in a Japanese tea, the more prized it is. Umami is a flavor that is a mix between savory and sweet, and has been compared to seaweed or sea creature.

I have a newfound respect for tea and all the work that goes into its creation thanks to this incredible experience. Tea farming is both a science and an art, and thankfully, a delicious one!

Mackenzie Lorkis studied in Kyoto, Japan in the Language & Culture, Doshisha Univ. Program – Spring 2018