BY JAZZ BROUGHTON

Memorials and memory spaces are popular ways that the lives of the disappeared go remembered. Often the memory sites have lists of names, photographs, or other artifacts that remind us of the lives that were lost during the brutal dictatorships of the seventies and eighties. Chile’s dictatorship under Pinochet began in 1973. Thousands of people were tortured and exiled and a small percentage of them were killed aka disappeared.

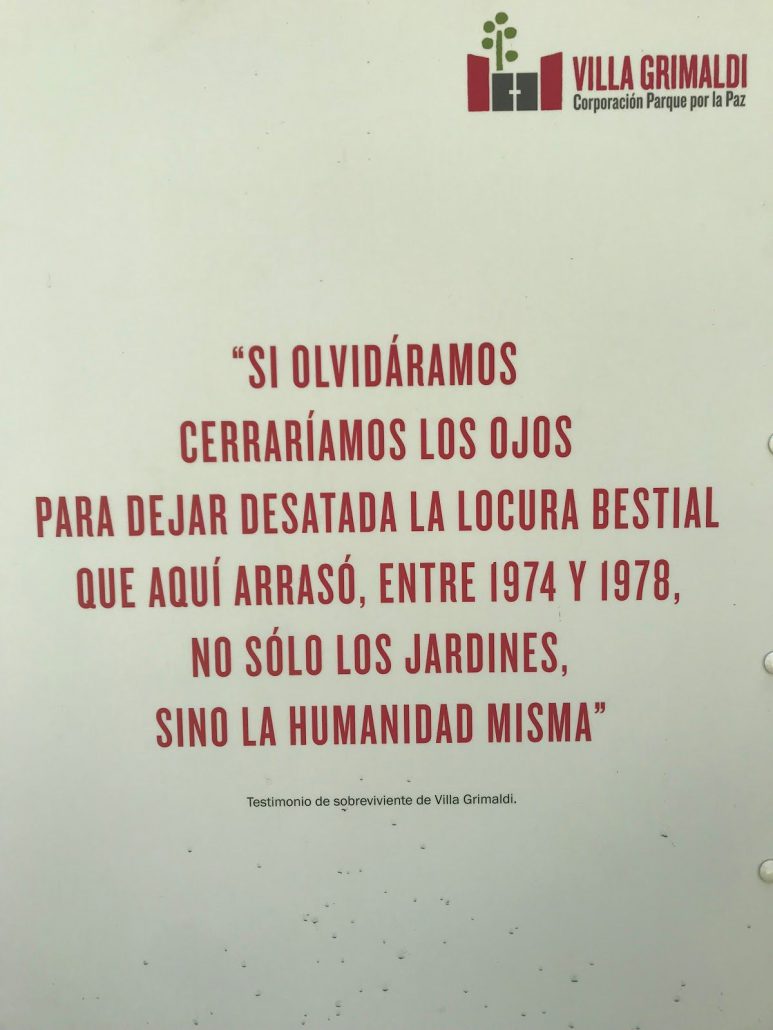

Memorials such as the one at Villa Grimaldi, where many of these photos were taken, are examples of how spaces once filled with torture, violence, and state terrorism can be transformed into spaces for healing, education, reflection, and community. Villa Grimaldi was a torture center during the dictatorship in Chile that began in 1973 and ended in 1990. Today, Villa Grimaldi has trees, fountains, a pool, and other parts of the memorial that are remainders of the dictatorship, but most of the site was destroyed. There is a rose garden that gives memory to the women who disappeared and a fountain to represent cleansing and recognition of those who were killed by death flights.

One thing that is common in nearly all of the memorials I visited is a section of the memorial or memory site to be designated to informing visitors on a brief history of the dictatorship and why there are names, testimonies, and photographs that represent something so much larger than I could understand. My classes often questioned who should create the memorials and who they should be made for. Some of the memorials/ memory sites we went to were Chile’s National Stadium,The Museum of Human Rights and Memory, and The General Cemetery.

The museum was very informative and shed light on connections between the violation of human rights in Chile to violation of human rights around the world. They had audios, videos, and other artifacts that brought me back in time and gave me a look into the horrors that took place during the dictatorship. Newspaper clips, coloring books, and life size images of people on the wall gave us something to hold on to, connect with, and feel. The difference between the museum and other sites for memory is that the museum was curated and has galleries that change throughout the year.

The cemetery on the other hand holds its memories and information like a box with a thousand keys. It cannot move nor can it be replaced. The cemetery provides us with a much more personal interaction with those who had been lost. It is not just seeing their names or watching interviews, it is being in the presence of their spirit and their area of rest.

While some may try their best to forget the past, the past lives through our present. It defines our today, but we get to write the definition. How do we heal from trauma and connect to our past while creating a sustainable foundation for our future? Memories provide us with context, hope, and a point of reference as we move forward.

We often discussed: how do we learn from memory? What do we do with the archives of our past? Does public symbology provide spaces for healing or reinstitute trauma?

Obstacles regarding memory and space are universal and can be seen throughout the world. We fight for representation of the Tongan people, the people of the land in which UCLA rests, and the people of South America fight for advocacy of the Mapuche people as well as other groups. Our memories of trauma and historical events vary depending on our community and time in life. We can utilize our memories as a community for social justice, art, and so much more.

Jazz Broughton studied abroad in Argentina and Chile in Fall 2018: http://eap.ucop.edu/OurPrograms/chile/Pages/human_rights_cultural_memory_buenos_aires_santiago.aspx?_ga=2.141667250.1203383737.1560395031-875334149.1560395031