BY NINA CHIKANOV

On September 28, 2017 I saw my first (and most likely last) bullfight at the Plaza del Toros de las Ventas in Madrid. A few days beforehand, my program organized an informational conference to explain the history of the fight and introduce us to the different people and phases we would see during the event. (Skip to “Reflections” if you are already familiar with bullfighting procedures, history, and terms!)

A Brief History

Bullfighting in Spain has origins as early as 711 AD, when a bullfight took place to honor King Alfonso VIII. The bullfight at the time was not the same one that takes place in Spain today, as the fight was reserved for selected members of the Spanish aristocracy / nobility and took place exclusively on horseback rather than on foot. In the early 1700s, King Philip V prohibited nobles from taking part in bullfighting, as he believed it created a “bad image” in front of the common people. Despite this ban, commoners continued to practice the sport on foot. Almost a century later, the present version of Spanish-style bullfighting was introduced by Franciso Roméro in Ronda, Spain at the beginning of the 19th century.

The 3 Stages and Roles of the Fight

The entire event lasts for around 2 hours, including an opening ceremony and 6 separate bullfights. Each matadero (bullfighter) has 6 assistants who make up a caudrilla (entourage), and each group fights two bulls by the end of the night. The separate fights are broken up into three stages, each of which makes it easier for the matadero to kill the bull. The entourage knows when to transition from one stage to the other by the sound of a bugle that rings throughout the stadium.

- Tercio de Varas (The Lancing Third)

Once the bull * is released into the ring, the banderillos and matadero test out the ferocity of the animal in the first third by teasing it with the capote (pink and gold cape). Essentially, a group of men wave their capes to make the bull charge in their direction before hiding behind a small barrier close to the edge of the stadium once the bull gets close enough. The matadero will then test the personality of the bull by making a few passes with his capote.

Next, two picadores (lancers on horseback) come into the arena. They stab the bull in the nape of its neck with a vara de detener (pike) in order to weaken those muscles and draw blood. This step in the process forces the bull to hold its head slightly lower during the following stages, which will ultimately enable the matadero to kill the bull cleanly during the third stage of the fight.

* The Spanish Fighting Bull is a special breed of bull known for its combination of aggression, energy, strength, and stamina. They are bred in large ranches in conditions as close to how they would live in the wild as possible. Since they typically reach maturity later than breeds of cow used for meat due to their muscular physique, bulls used in the fight are 4 – 6 years old. (Remember that these bulls are a special breed — this fact is used by many to justify the fight).

2. Tercio de Banderillas (The Third of Banderillas)

In the second third, each of the three bandilleros (men with colorfully decorated and short darts) stick two banderillas (the darts) in between the bull’s shoulders. This third further agitates, angers, and weakens the bull.

3. Tercio de Muerto (The Third of Death)

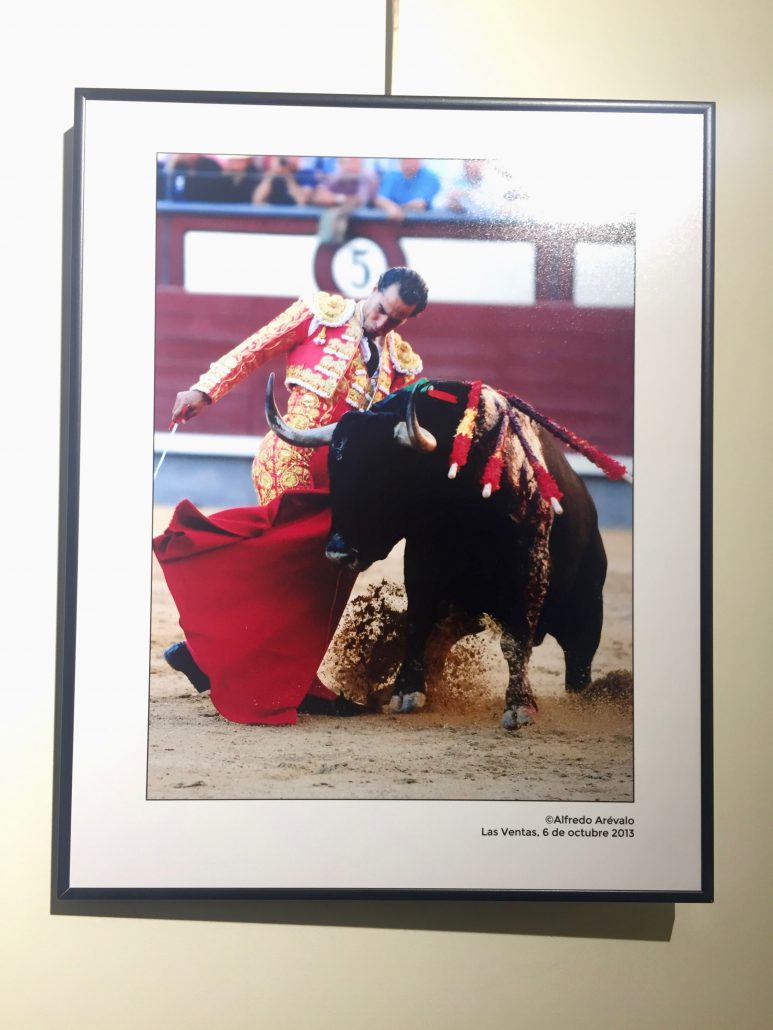

The final stage is a standoff between the bull and the matadero armed with a muleta (red cape) and espada * (sword). The bullfighter draws in the animal with his cape, trying to get as close to the bull as possible while guiding it around him. This ritual continues to tire out the bull and is considered the primary art form of bullfighting, as many claim that the movement of the bullfighter coupled with the danger of proximity between the two subjects shows the intimate relationship between human and beast. Ultimately, the matadero tries to maneuver the bull into a position where he can (ideally) cleanly stab the bull through the shoulder blades and into through the aorta and the heart for a quick death.

* The bullfighter originally starts with a wooden sword, since it is light and easy to maneuver, and then switches it out (with the help of his mozo de espadas, or sword page) for a real blade once he is ready to end the fight.

Closing Ceremony

After the death of the bull, three horses bring the corpse around the perimeter of the stadium towards the exit, and the sand is prepared for the next match.

Rituals & Prizes

Sometimes, although very rarely (especially in Madrid, since the stadium is one of the most prestigious out of the the four stable rings in Madrid, Sevilla, Granada, and Aranjuez), a bullfighter performs extremely well (see: has good technique, cleanly kills the bull) and is rewarded with either one ear, two ears, or two ears and the tail of the bull. Even more rarely, the matador will be carried out of the stadium by the crowd. Receiving any of these prizes is a high honor, and is ultimately decided by the president and the spectators.

At the end of a fight, if a matadero performs particularly well, supporters will stand up and wave white handkerchiefs to signal to the president that they think the fighter deserves a prize. The president takes this into consideration and then makes the final decision.

During the fight, there are also certain signs of approval or disapproval from the crowd. The way a spectator claps/whistles for the matadero determines their mood. Claps of approval are normally quicker and shorter, while claps of disapproval have longer pauses in between and sound more hollow. From my experience, the latter form of clapping occurs if:

- The matadero does not get close enough to the bull while making passes with his cloak.

- The picadores or banderillos do not pierce the bull in the proper area of its back when inserting pikes or darts.

- The matadero does not successfully hit through the heart of the bull the first time, resulting in a prolonged death.

Overall, angry claps/whistles condemn sloppy or improper technique of the matadero and his entourage.

Reflections

Before September 28, I never saw man kill an animal with my own eyes. We were forewarned that six bulls would die during the fight, but hearing about it and seeing it are two completely things.

Watching the first bull fight was especially horrifying, especially since I did not expect poor technique from the matadero.

The bull ran out into the center of the ring at full speed, immediately chasing the first capote it saw until the cape suddenly disappeared behind a wall. Confused, the bull wandered until it saw another capote and ran after that one, just to have the same happen as the man ran behind the wooden shield. Sometimes, the bulls were smart and tried to get around the wall to pursue the moving object, but their horns were too wide to fit in between the crevice of the guard and the wall. I could only imagine the bull’s frustration when it thought the target was within reach, then suddenly disappeared without a trace.

When the picadores came out with their pikes and stabbed the bull in the nape of its neck, most bulls rammed straight into the horses that the picadores were riding. After some seconds of struggle, they would wait for the man to remove the pike and run towards the next cape they saw. After the hit, you could clearly see the blood matting the bull’s skin, even from the top levels of the arena.

The insertion of the six decorated darts by the bandilleros thankfully was over with quicker than the hits on horseback. By this point, though, you could see the bull obviously breathing harder, its stomach heaving with every breath. It was struggling but persevering to fight nonetheless. At this point I realized how majestic this animal was. To endure such pain showed its strength, its personality, its desire to live.

The final third, with just the matadero and the bull was the most problematic for me. This third is also the third that is most important for the matadero score-wise. It does not matter how bad his technique or the technique of his team is up until this third. If he doesn’t show mastery in the final third, there is no chance of acquiring the coveted prize of the ear.

The relationship between the matadero and the bull in the final third was described to me beforehand as an art, not also because of the elegant movement of the bullfighter, but also because of how man could control beast in this section. The closer the proximity between the fighter and the animal, the higher the stakes, the higher the appeal, the higher the artistic value.

I acknowledge that there are some artistic characteristics in the movement of the matadero, since he moves as if he were the lead in a dance and the bull his partner. It does seem elegant, and if the bullfight solely consisted of the part where the fighter and the bull dance with each other, I would likely hold different opinions. The problem, for me, comes from the attitude of the bullfighter.

If he controls the movements of the bull well enough to warrant loud “Olé”s from the crowd, the matador presents himself very pompously. He approaches the bull slowly and tauntingly, arching his back and leading with the muleta. In a series of movements that may be best described as erotic, the matador exposes himself in front of the bull, flirting with the idea of death and asserting his dominance over the animal at the same time.

Some people call this a display of courage. They point to this third when they describe bullfighting as an art. They savor the omnipresent danger that exists in the possibility that the bull may gore the bullfighter at any moment.

Personally, I see bullfighting as man’s attempt to control, manipulate, and assert his dominance over nature. The human race is by no means the strongest out of all the creatures that exist in the world. But as intellectual beings, we’ve built up an idea of superiority in our minds. Man is superior to all other things. Man is capable of thought, therefore man is in charge of the world. All things on Earth and beyond should bow to man, for man is supreme.

Through the matador‘s pompous approach to teasing the bull, we see this ideal of superiority shine through. But even in the context of bullfighting, our assertion of dominance is a hoax. Without the first two thirds of the bullfight, there is no way the matadero would stand a chance against the majestic creature before him. Only after sufficiently weakening and tiring out the bull does he stand any possibility of winning. And when this chance is given to him, he taunts the bull like an arrogant school-kid.

Under different circumstances, man is not more powerful than beast. And for this reason, bullfighting is a pure manipulation of nature to perpetuate our dominance over Earth and its creatures. It may be the largest display of ego I have ever experienced in my almost 20 years in the world.

…

You may have noticed that I use the term “bullfight” often without any qualifiers. Should I call it “the art of bullfighting” when the artistic bit of the whole spectacle serves to bolster our egos and our perceptions of dominance? Should I call it “the sport of bullfighting” when the competition is unfair and the trophy is death?

I’ve been struggling to find some appreciation for the cultural importance of the bullfight for Spain. A country’s culture should reflect the values of its people — I do not think that the values of modern Spaniards at all match those exhibited in the fight.

The most grotesque display of power comes at the end, when it is time for the matadero to stab his sword straight through the bull’s heart. If done properly, the bull should die in seconds. However, this is rarely done as it is intended to be, and the animal can suffer for minutes more, having to endure undue stress in the last moments of its life. During the entire process, the matadero stands proudly in front of the bull with his arm up, as if paying his final respects. He did it. He challenged nature, and he won.

…

I went to the bullfight because I was intrigued. I stayed through the whole thing to try to grasp a deeper understanding of the tradition and the culture. By the end, I was focusing solely on the technique of the matadero, hoping that he would have proper form and avoid causing the bull any more suffering than it had to endure.

I saw 6 bulls die on September 28 and I know many more have died on the same sand. Supporters of the bullfight see the death as a rite of passage. Since the Spanish Fighting Bull is a special breed of bull, supporters argue that this species would die out if it were not for the bullfight. I wonder, though, if 4-6 years of a “good life” is worth the 20 minutes of exhaustion, spectacle, and pain of the bullfight. For me, it’s definitely not. By keeping this breed alive, we are fighting against the natural order of the world. Death is bound to happen, but bullfighting glorifies death at the expense of nature.

If nothing else, the experience provoked some interesting thoughts:

- Why are humans so mystified with violence? With death?

- Does culture perpetuate atrocity? At what point do modern values overshadow ancient tradition?

- Does cultural change only occur with the maturation of a new generation?

- Should I feel the need to become a vegetarian? What is the core difference between killing animals for spectacle versus for consumption for me?

I don’t regret going, yet the lives of those six bulls burden my conscious. I wonder when the eradication of the bullfight as it exists today will come and how the views of the world will be different when it does.

Nos vemos pronto,

(We’ll see each other soon)

Nina

Nina Chikanov studied abroad in Madrid, Spain in fall 2017: http://eap.ucop.edu/OurPrograms/spain/Pages/contemporary_spain_madrid.aspx